All of our breeding cats are blood tested for FeLV and FIV and DNA tested by Neogen for PRA, PKD, PKdef, CEP and more.

All of our breeding cats have their kindeys checked by ultrasound once and their hearts ultrasound checked yearly for HCM until they are at least 6 years old, even after they have been neutered.

All of the kittens we sell have a DNA profile and are parentage verified through DNA by Combibreed.

Please take your time to find out why we do this and why this is so important.

HCM : Hypertrofic Cardiomyopathy

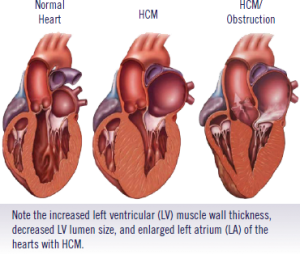

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM)

is the most common form of heart disease in cats and occurs where there is an increase in the thickness of the muscular wall of the heart. This reduces the volume of blood within the heart and also prevents the heart muscle relaxing properly between contractions.

Early signs of heart disease

In the initial phase of disease, cats may show no signs at all and appear completely normal. In fact a number of cats with cardiomyopathy may never actually develop clinical disease. However, while in some cats progression of the underlying disease is slow, in others it can be quite rapid.

Early warning signs that your vet might detect include:

- Presence of a heart murmur – this is an abnormal noise your vet can detect when listing to your cat’s heart with a stethoscope and develops due to turbulence in the flow of blood through the heart.

- Presence of a gallop rhythm – during each cycle of heart contractions, normally you can hear two sounds when you listen to the heart with a stethoscope (these sounds are associated with closure of heart valves during contraction and relaxation of the heart). With significant heart disease, a third audible heart sound is sometimes detected and this is referred to as a ‘gallop sound’ or ‘gallop rhythm’.

- Abnormalities in heart rate – with heart disease, the heart rate can sometimes significantly increase or decrease outside of the normal range for a cat, and sometimes there may be heart beats without any effective flow of blood (a heart beat but no pulse detectable in an artery (known as a ‘pulse deficit’)).

- Presence of cardiac rhythm disturbances – these are also referred to as cardiac dysrrhythmias. Normally, cats have a very regular heart rate, however with heart disease there can be interference in the normal electrical impulses that control heart contractions; this can lead to disturbances to the normal rhythm.

Many cats, especially those in the early stages of the disease, may only have changes in the cardiac muscle that are detected during ultrasound examination of the heart. These cats are clinically silent (or asymptomatic), although many will go on to develop signs later on.

Heart failure

If heart function is significantly impaired by cardiomyopathy, this will lead to heart failure where there is compromise to blood flow through the heart and blood output from the heart.

Cats can sometimes develop clinical signs without prior warning, and some cats can deteriorate very rapidly. Some cats with heart disease show signs of collapse, or ‘fainting’. However, this is relatively uncommon and usually associated with marked disturbances to the normal rhythm of the heart (which can lead to episodes where the brain is starved of oxygen through poor blood flow).

In cats, the most commonly seen sign of heart failure is the development of difficult breathing (dyspnoea) and/or more rapid breathing (tachypnoea). This is generally caused by either a build up of fluid in the chest cavity around the lungs (called a pleural effusion), or due to a build up of fluid within the lungs themselves (called pulmonary oedema).

Feline aortic thromboembolism (FATE)

Another sign which can occur in cats, and may sometimes be the first indicator of underlying heart disease, is the development of what is known as ‘feline aortic thromboembolism’ or FATE. A thrombus (blood clot) may develop within one of the heart chambers (usually left atrium) in a cat with cardiomyopathy. This occurs mainly because the blood is not flowing normally through the heart. The thrombus, or clot, is initially attached to the wall of the heart, but may become dislodged and be carried into the blood leaving the heart. A thrombus that moves into the blood circulation is called an embolus, hence the term ‘thromboembolism’. Once in the circulation, these emboli can lodge in small arteries and obstruct the flow of blood to regions of the body. Although this can happen at a number of different sites, it more commonly occurs towards the end of the major artery that leaves the heart (the aorta) as it divides to supply blood to the back legs. This complication is seen most commonly with HCM, and will cause a sudden onset of paralysis to one or both back legs, with severe pain and considerable distress.

Differentiation of forms of cardiomyopathy

Various diagnostic tests can be done to assist the diagnosis of heart disease in cats.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG) – this is an electrical trace of the heart activity. It can be very useful for the detection of cardiac rhythm disturbances, but has more limited use beyond that.

- Radiography (X-rays) – are helpful for showing changes in the overall shape and size of the heart, and for detecting a build up of fluid (pulmonary oedema or pleural effusion). Repeating radiographs may also allow monitoring of the efficacy of any treatment.

- Heart ultrasound (echocardiography) – is very helpful as it allows a view of the internal dimensions of the heart, the wall thickness, and the contractility of the heart to be assessed. It can also show where a heart murmur is originating from. This is the only test which can readily distinguish between different types of heart disease in cats. Although a small area of skin usually needs to be shaved to perform ultrasound, the procedure is not uncomfortable or painful and so can be performed in most cats without any sedation or anaesthetic.

Treatment

Where heart failure develops, various drug treatments may be available to help improve and manage the condition. These may include drugs such as:

- Beta-blockers such as atenolol or propranolol, which slow down the heart rate and reduce the oxygen demand on the heart.

- Diltiazem – this drug is known as a ‘calcium-channel blocker’, and reduces both heart rate and the strength of heart contractions. It reduces the oxygen demand of the heart and may help the heart muscle to relax between contractions

- ACE-inhibitors – help block the activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) – a hormone system stimulated in cats with heart disease. Their use may help in the management of heart failure and possibly also in earlier stages of heart disease.

o Diuretics (such as frusemide/furosemide) – these are extremely valuable once signs of congestive heart failure develop, to help remove the fluid build up in or around the lungs.

Unfortunately the true effectiveness of many drugs in treating heart disease in cats is unknown, and more clinical trials are needed. Different drugs also act in different ways, and so may be helpful in different situations. In general, diuretics are the most useful drugs in managing signs of congestive heart failure,. With early diagnosis of heart disease, treatment may help to slow or delay its progression and help to maintain a good quality of life.

We lost our best buddy Barça to HCM

Helaas weten wij zelf maar al te goed wat HCM inhoudt.

Onze lieve Britse Korthaar Barça d’Or of Bedrock was op de leeftijd van 14 maand aan mooie showcarrière bezig en zou van een macholeventje als dekkater beginnen genieten.

Vol goede moed lieten wij onze kater testen op Felv, FIV en bloedgroep. Hij testte op beide negatief en had bloedgroep A.

Hiermee waren wij natuurlijk zeer tevreden. Ook de PKD-test was negatief.

Hartverscheurend was echter de diagnose dat Barça HCM had. Dit was reeds op 14 maand duidelijk zichtbaar op de echo bij dr. Putcuyps.

Barça moest alle stress vermijden, dus einde showcarrière.

Wij lieten hem zo snel mogelijk castreren en zelfs de castratie hield voor hem een gezondheidsrisico in.

Het werd een moeilijke periode met driemaal daags Furosemide, een vochtafdrijver om het vocht uit zijn longen te proberen houden en iedere morgen een spuitje Prilium “siroop” tegen hartinsufficiëntie. We zorgden ervoor dat er telkens ‘s morgens, ‘s middags en ‘s avonds iemand van het gezin naar huis kon om Barça’s medicijnen toe te dienen.

Hij was nog steeds heel gelukkig en wilde verder leven! En wij wilden natuurlijk onze lieve teddybeer niet kwijt.

Helaas werd het ziektebeeld na verloop van tijd duidelijker.

Barça werd sneller moe en kortademig. Bij drukte om zich heen begon hij al snel te hijgen.

Hij at nog goed, speelde en spinde, maar we merkten dat hij het moeilijker kreeg.

Op de leeftijd leeftijd van 2,5 jaar kreeg Barça een trombose in de achterpoten en raakte verlamd.

We dachten dat het voorbij was, maar als bij wonder en met een fikse portie wil om te leven is onze sterke kater hier terug doorgesparteld. Na 2 dagen wankelde hij opnieuw op zijn pootjes en na een week sprong hij opnieuw op schoot.

Wij waren dolgelukkig en begrepen maar al te goed dat hij door het oog van de naald was gekropen.

Enkele maanden later sloeg het noodlot opnieuw toe en moesten we afscheid nemen van een prachtige kat die ons nog geen 3 volle jaren met zijn gezelschap mocht verblijden. Dit wensen wij niemand toe.

Hadden wij Barça niet getest op HCM, dan had hij sowieso 1 of 2 nestjes kittens verwekt alvorens wij enige uiterlijke verandering aan hem hadden kunnen merken. Zijn kittens zouden een grote kans op HCM gehad hebben en dit zou alweer veel verdriet hebben opgeleverd bij nieuwe baasjes.

Het is moeilijk om op deze manier met je neus op de feiten te worden gedrukt over het belang van HCM-tests, maar wij hopen dat ons verhaal over Barça mensen twee keer doet nadenken alvorens niet-geteste kittens aan te schaffen.

Een HCM-test geeft geen 100% uitsluitsel, maar zonder test speel je russian roulette.

Wij hopen dat op termijn alle HCM-besmette katten uit de fok kunnen gehaald worden zodat niemand dit nog hoeft mee te maken.

PKD: Polycystic Kidney Disease

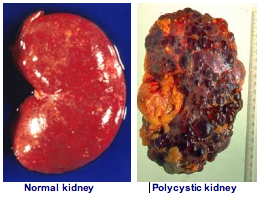

What is polycystic kidney disease?

Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (AD-PKD) is an inherited condition that causes multiple cysts (pockets of fluid) to form in the kidneys. These cysts are present from birth but initially are tiny. Over time they grow progressively larger to the point where they severely disrupt the normal kidney tissue. When there is sufficient interference with normal kidney function, chronic kidney disease (CKD, or renal failure) will develop.

The cysts usually grow quite slowly, so most affected cats will not show any signs of kidney disease until they are middle-age or older, typically at around seven or eight years of age. However, in some cats kidney failure will occur at a much younger age and at the moment there is no way of predicting how rapidly the disease will progress in any particular cat.

How is PKD inherited?

AD-PKD is the result of a single, autosomal, dominant gene abnormality. This means that the disease is controlled by a single pair of genes and:

- Every cat a copy of the abnormal (mutated) gene will have AD-PKD; there are no unaffected carriers of the gene.

- Every cat with AD-PKD will have the abnormal gene, even if that cat only has a few small cysts in its kidneys.

- A cat only needs one of its parents to be affected with AD-PKD in order to inherit the abnormal gene.

- Every breeding cat with AD-PKD will pass the disease on to a proportion of its kittens, even if it is mated with an unaffected cat.

How can I find out if my cat is affected?

Testing for AD-PKD can be done in two ways:

- A gene test is available which accurately identifies all cats with the abnormal gene. This test can be run on a blood sample, or a mouth swab. This is a simple and very accurate test and can be performed on a cat of any age. International Cat Care believe that whenever genetic tests are run on cats for the selection of breeding stock, the gene test result should be linked to a method of permanently identifying the cat that has been tested (e.g., a standard, internationally recognised microchip number).

- The disease can also be identified by ultrasound scanning of the kidneys. In advanced disease the cysts are large and the diagnosis is straightforward, but it can be difficult to identify the cysts in young cats (ie, before breeding age) so for reliable pre-breeding diagnosis the scan must be undertaken by a specialist veterinary ultrasonographer, using a very high definition ultrasound probe, and the cat must be at least 10 months old. Unfortunately this limits the availability of this testing method.

Can PKD be cured?

Unfortunately there is no treatment that will prevent the development of chronic kidney disease in a cat that is affected by PKD. The cysts are present from birth and cannot be removed, nor can they be prevented from growing.

Once kidney failure has developed, supportive treatment can be used to minimise the impact of the kidney disease, but it will inevitably be a progressive disease.

Do all cats with PKD die of kidney failure?

The number of cysts present in each kidney, and the rate at which the cysts grow, varies considerably from cat to cat. Severely affected cats or cats with rapidly growing cysts will develop chronic kidney disease at an early age, and will die from PKD. Most affected cats will appear to be quite healthy until later in life but will eventually succumb to renal failure and die from PKD. Some cats with few cysts or slowly growing cysts may remain healthy into old age, and may die from other conditions before kidney failure develops.

What can be done about PKD?

All cats that carry the abnormal gene are affected with AD-PKD, and affected cats should be identified before they reach breeding age. The availability of the gene test makes it relatively easy to eliminate the disease provided all cats are tested before being used in a breeding program.

Finding an AD-PKD negative cat

If you are considering purchasing a pedigree cat of a breed known to be affected by AD-PKD, it is sensible to request to see evidence that both the queen and tom cat used to produce the litter of kittens have been tested for AD-PKD and are negative. If both were negative then the litter of kittens should all be negative. If in any doubt about whether cats have been tested, or the interpretation of a test result, just contact your vet.

FIV: Feline Immunodeficiency Virus or cat’s AIDS

What is FIV and how is it spread?

Feline immunodeficiency virus belongs to the retrovirus family of viruses in a group called lentiviruses. Lentiviruses typically only cause disease slowly and thus infected cats may remain healthy for many years.

Once a cat has been infected with FIV, the infection is virtually always permanent (cats cannot eliminate the virus), and the virus will be present in the saliva of an infected cat. The most common way for the virus to be transmitted from one cat to another is via a cat bite, where saliva cottoning the virus is inoculated under the skin of another cat.

How does FIV cause disease?

FIV infects cells of the immune system (white blood cells, mainly lymphocytes). The virus may kill or damage the cells it infects, or compromise their normal function. This may eventually cause a gradual decline in the cat’s immune function.

How common is FIV infection?

The prevalence (frequency) of FIV infection varies in different cat populations. It tends to be more common where cats live in more crowded conditions (and thus where cat fights are more common) and tends to be much less common where cat populations are low and where cats are kept mainly indoors

What are the clinical signs of an FIV infection?

FIV usually causes disease through immunosuppression – the normal immune responses of the cat are compromised, leading to an increased susceptibility to other infections and diseases.

Some of the most common signs seen in FIV infected cats are:

• Recurrent fever

• Weight loss

• Lethargy

• Enlarged lymph nodes

• Gingivitis and stomatitis (inflammation of the gums and mouth)

• Chronic or recurrent respiratory, ocular and intestinal disease

• Chronic skin disease

• Neurological disease (in some cats the virus can affect the brain)

How is FIV diagnosed?

There are several tests available for diagnosing FIV infection, some of which can easily be performed in your own vet’s clinic. Most tests involve collecting a blood sample and detecting the presence of antibodies in the against the virus.

Advice for breeding colonies

To minimise the risk of introducing FIV into the colony, breeders should prevent their cats having free access outdoors, or having contact with cats allowed outdoors. Annual testing of breeding cats is ideal, but testing any new cats before being introduced to an FIV-free colony is vital. If any cats test positive for FIV they should be removed, the colony isolated, and the remaining cats retested after 3-6 months.

Prognosis for infected cats

The prognosis for FIV-infected cats is guarded, but depends on the stage of disease. If FIV is diagnosed early, there may be a long period during which the cat is free of clinical signs related to FIV, and not all infected cats go on to develop an immunodeficiency syndrome. Infection is almost invariably permanent, but many infected cats can be maintained with a good quality of life for extended periods.

FeLV: Feline Leukaemia Virus

What is FeLV and how is it spread?

Feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) belongs to the retrovirus family of viruses, in a group known as oncornaviruses. Oncornaviruses are a group of viruses that cause development of cancers, among other effects.

FeLV is an important cause of disease and death in cats. In a cat persistently (permanently) infected with the virus, there is significant risk of developing many severe illnesses such as anaemia, immunosuppression and cancer. It has been estimated that 80-90% of infected cats die within 3-4 years of FeLV diagnosis.

In a persistently infected cat, large quantities of virus are shed in the saliva, and potentially the faeces, urine and milk. The virus is fragile and does not survive in the environment for any length of time. It is thought that infection is perhaps spread most commonly through prolonged social contact (mutual grooming, sharing of food bowls, litter trays etc., where virus may be ingested). However, the virus can also be transmitted through biting and if an entire queen is infected with FeLV, any kittens she produces will also be infected (although many die or are are aborted/resorbed before birth).

In general, less than 1-2% of healthy pet cats are infected with FeLV, however the infection is found more commonly in sick/outdoor cats, and it is slightly more common in males.

Effects of FeLV infection

The most common effects of progressive FeLV infections (persistent viraemia) are:

Immunosuppression – suppression of normal immune responses. This accounts for around 50% of all FeLV-related disease and allows for development of secondary diseases and infections

Anaemia – FeLV-related anaemia can develop in a number of ways, including viral suppression of the red blood cell precursors in the bone marrow. Anaemia accounts for around 25% of all FeLV-related disease

Neoplasia – FeLV infection can damage the DNA (genetic material) of infected cells and can lead to development of tumours (most commonly lymphoma or various leukaemias). This accounts for around 15% of FeLV-related disease. Although neoplasia is only a part of the disease spectrum caused by FeLV, an FeLV-infected cat is approximately 50 times more likely to develop lymphoma than a non-infected cat.

Other diseases – a variety of other diseases including skin disease and reproductive failure develop in some infected cats.

Signs of FeLV infection

Immunosuppression is the single biggest cause of clinical signs in FeLV infected cats. Typically a variety of chronic (persistent) and/or recurrent diseases develop in these cats, with progressive deterioration in their condition over time. These features all suggest a progressive deterioration in the cats immune response and ability to deal with other diseases or infections. Clinical signs are extremely diverse but include fever, lethargy, poor appetite, weight loss, and persistent or recurrent respiratory, skin and intestinal problems.

Diagnosis of FeLV infection

Fortunately, good diagnostic tests are readily available for FeLV. Simple ‘in clinic’ blood tests are used by many vets. These tests are quick, relatively inexpensive, and generally very reliable. Often the kits simultaneously test for FIV, as many of the clinical signs of FIV infection are similar to FeLV infection.

Any cat that tests positive for FeLV should be isolated from other cats to prevent transmission.

Treatment of FeLV infection

There is no cure for FeLV infection, and management is largely aimed at symptomatic and supportive therapy.

Prognosis

For a persistently infected cat, the prognosis is very guarded. In one study FeLV infected cats survived on average around 2.5 years after their infection was diagnosed, compared with around 6.5 years for similarly aged uninfected cats.

Source: icatcare.org: International Cat Care